Simulating Brazil Nut Algorithm on Kilobots

December 8, 2015

Introduction

This project focuses on adapting the robotic swarm segmentation algorithm described in the referenced paper[1] to a simulated swarm of kilobots. This algorithm is based on the Brazil Nut effect and was and was previously implemented on a swarm of e-puck robots.

Brazil Nut Effect

The Brazil Nut effect this algorithm is based on describes the self sorting behavior observed when random motion is applied to a heterogeneous mixture of finite particles (such as a bowl of mixed nuts). Specifically, the larger particles rise to the surface of the mixture.

To implement this effect on a swarm of robots, three key components were identified and modeled[1]; an attractive (gravitational) force, a repulsive force from neighbors, and random motion. The sum of the vectors produced from these forces gives the robots their motion vector.

Videos

The follwoing videos show the algorithim running on a kilobot simulator written by Professor Michael Rubenstein.

Adapting to Kilobots

When this algorithm was implemented on e-pucks[1], light sensing was used for the attractive force and the distance and orientation to neighbors was sued for the repulsive force. To get a heterogeneous mixture, robots were assigned two different artificial radiuses that they used to determine if they were close enough to a neighbor to apply a repulsive force.

Unlike the e-pucks though, the kilobots have no orientation sensing relative to neighbors, although they can measure absolute distance by passing messages. The kilobots move by spinning one or both side mounted vibration motors, which allow them to move forward, turn counter-clockwise, or turn clockwise.

Like the e-pucks, the kilobots can detect a light source, so the attractive force could be implemented in largely the same way. If the robot detects the light source, it is facing the light. So the algorithm has the robot move straight if it detects the light source, and otherwise it turns counter-clockwise.

The repulsive force is implemented by having the robot check the distance to any neighbor it receives messages from. If that distance is less than its artificial radius, it turns clockwise. Since the light following has the robots moving in a predominantly counter-clockwise motion, this usually lets the robot move away from the close neighbor.

Finally, random motion was added by having the robot periodically ignore any changes to the motion command for a random amount of time. During this time, the robot continues to move however it was before the random motion timer started. THis has the effect of changing the robot’s’ heading and position in a way that isn’t directly related to the gravity force or the neighbor avoidance force.

Results

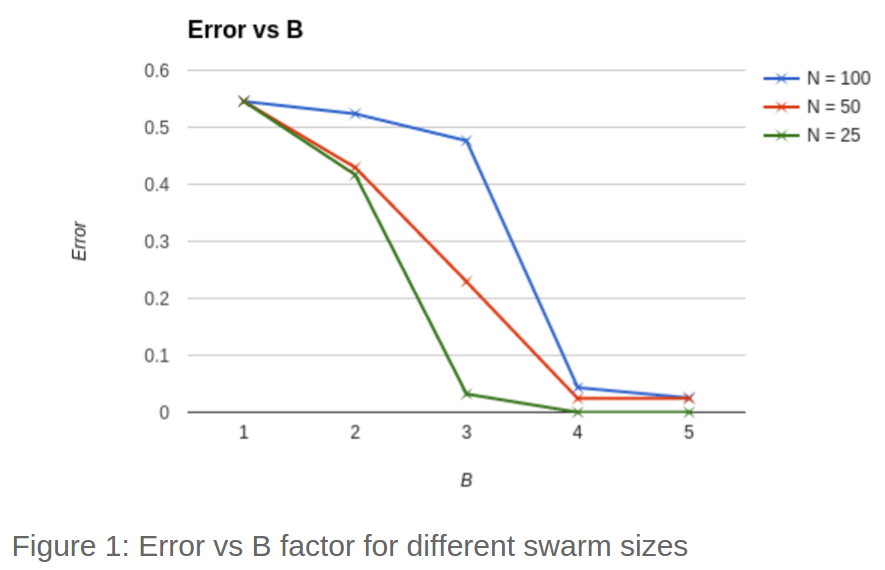

Using the same performance metric as [1] to calculate error where 0.5 is a roughly random distribution and 0 is perfect convergence, swarms of 25, 50, and 100 robots. B is the ratio between the small and large artificial radiuses used by the robots where r2 = b*r1. As shown in figure 1 below, these results roughly mirror the results from the original paper[1] in that convergence gets better as b increases. However, there are clearly some differences.

Implemented this way on kilobots, the algorithm seems to have more susceptibility to robot self-interference. This is indicated by the fact that convergence improves as swarm size decreases.

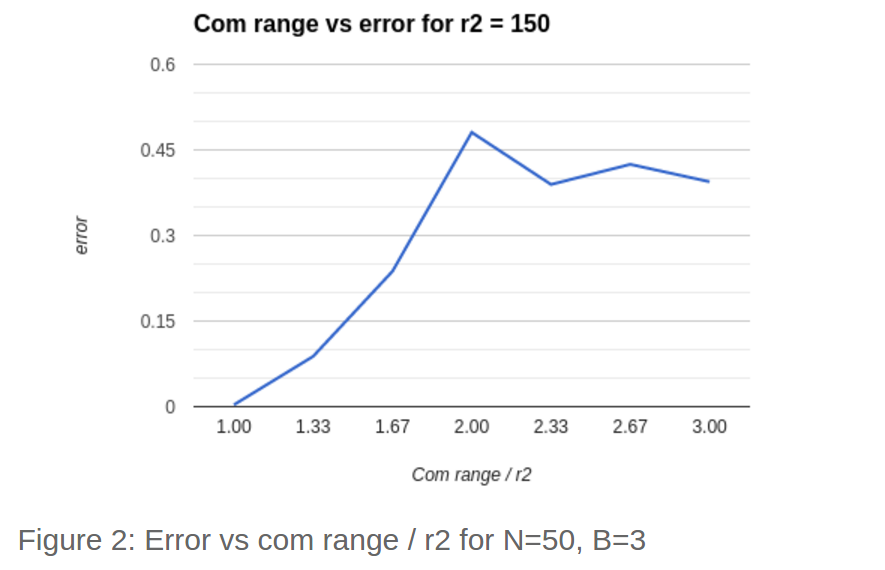

It is also worth noting that how well the swarm converges seems to be dependant on the ratio between the large radius, r2, and the com range (farthest distance robots can talk). As figure 2 below shows, as this ratio increases from 1, error also increases. Also, this ratio should never be less than one as that would indicate an r2 value greater than the max communication distance.

This relation partially explains the large error in small values of B in figure 1, as all those experiments were performed with a constant com range that was greater than r2 at B=5.

Discussion

This project aimed to implement the Brazil Nut algorithm on a swarm of kilobots. Because kilobots lack the orientation sensing of the e-pucks from the original paper[1], this required adapting the algorithm to the capabilities of the new robots. From the results, this has been successful as a swarm of up to 100 kilobots running this algorithm with two different artificial radiuses can converge with an error value very close to 0.

Still, this implementation is highly sensitive to the swarm configuration. Specifically, ratio between the maximum communication range and the largest artificial radius directly affects convergence. Additionally, large swarm sizes decrease overall convergence due to robot self-interference.

Generally, this could indicate that removing orientation sensing makes this algorithm overall less robust. Of course that is traded for implementation on a simpler, cheaper platform which could theoretically increase scalability.

References

[2] Videos: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLCdzwz9McX2M9hMtn8ja1Q7sg_Y_MAOyy